Whether it’s getting a promotion, moving into a shiny new office, or finally hanging up your well-earned diploma after years of hard work, there are plenty of moments in a therapy career when it’s easy to succumb to the feeling that you’ve made it. These are the moments when you’re sure of yourself, when you feel like you’re firing on all cylinders, and the path in front of you appears clear and stable. But sometimes, the biggest career transformations happen when you least expect them. In the blink of an eye, everything you think you know about therapy can get turned upside down. For me, it happened Down Under.

Eight years ago, I got off a rickety white bus and dropped my backpack onto the red clay of the Australian outback. It landed with a foreboding thud, covering my boots in a thin film of dust.

Following close behind was a group of 10 Indigenous teenagers, all young women, as well as Sarah, a fellow therapist. We’d be spending the next eight days out here, hiking nearly 60 miles in total, moving from campsite to campsite as part of an outdoor therapy program I’d been tapped to lead.

As the teens took stock of their camping gear, chattering excitedly, I squinted in the blistering heat and gazed into the distance. I’d heard this land could be unforgiving. Now I knew why. By day, temperatures easily surpassed 100 degrees Fahrenheit. At night, they dropped near freezing. Never sleep in a dry creek bed, I’d been warned. Flash floods could strike at any moment. If that wasn’t enough, these parts were filled with some of the world’s most venomous snakes.

As the bus sputtered back to life and drove off, leaving a chalky cloud in its wake, my stomach sank. We were 11 hours from the nearest town. For the first time in my career as a therapist, I felt truly unmoored.

“All right!” I said, with as much enthusiasm as I could muster. “Let’s get started!”

A New Beginning

I moved to Adelaide, South Australia, in 2014. I was 23 at the time, and had just gotten my bachelor’s degree in social work. I was an eager practitioner, looking to take the first big step in his career, but that wasn’t why I’d gotten on a plane and flown for more than 19 hours. I’d done it for love, after I’d met an Australian woman named Renee on a cruise ship along the Alaskan coast.

“You should visit Australia sometime,” she said with a wink.

I’d gotten used to life on the go. Since 2005, I’d been working as a wilderness therapy guide for a nonprofit providing free outdoor therapy to marginalized youth. I’d take kids on weeks-long expeditions through the woods of West Virginia, Alaska, and North Carolina, interspersing therapeutic chats with canoeing, rock climbing, and hiking. I quickly grew into my role, not just as a therapist, but as a host, adventure guide, safety officer, and teacher.

It was an unusual lifestyle choice, one that had often frustrated my ex-girlfriend and eventually led to the demise of our relationship. And, quite frankly, it didn’t pay the bills. A few months after the cruise, I was broke, single, and had just received a birthday check from my grandmother—enough for a one-way plane ticket to Adelaide. I decided to take a leap of faith. I called Renee.

“So about that invitation,” I began. “Were you serious?” Apparently, she had been.

When we got married, I found myself searching for work in a place I hardly knew: a place where therapy might look very different from everything I’d learned before.

The World that Raised Me

As a teenager, I’d found desperately needed solace in the outdoors. My parents divorced when I was 10. My father, a Yugoslavian refugee, struggled with substances for most of his adult life. Not long after crashing his company truck in his tenth DUI, alcohol took his life.

In the summer months, my mother would send me to camp in Vermont—one of the few places we couldn’t butt heads. I fell in love with canoeing, building campfires, and living in rustic cabins. My first year away, I wrote a letter home, begging her to let me stay longer. In the wild, I thrived. I won awards, made friends, and family conflict faded into the background.

When I finally, barely, graduated from high school, I decided to pursue a career in outdoor therapy. I was convinced that the outdoors could help kids because it had helped me. Becoming an outdoor therapist felt like an honorable life’s work.

I soon learned that wasn’t exactly the truth.

The Problem with Outdoor Therapy

What comes to mind when you hear outdoor therapy? Canoeing on a placid lake? Meditating to sweet birdsong? Heartfelt confessions around the campfire? Chances are it’s not the poorly regulated kidnapping of troubled youth in the middle of the night, involuntary treatment, or a serious lack of transparency. But sadly, that’s the reality for many U.S. programs that claim to do outdoor therapy—and claim to be trauma informed.

Early in my career, I worked for these programs. Strip searches were commonplace, as was the use of restraint on unruly kids. We therapists were told to monitor conversations between kids closely. And before bedtime, we were instructed to take boots, belts, razors, and any objects that kids might use to harm themselves. Sentimental items, too, like the necklace we took from a girl who’d inherited it from her recently deceased grandmother.

We were also instructed by senior staff not to tell kids when these trips would be ending.

“How long is the hike?” one of the kids might ask.

“You’ll know when it’s over.”

“How long is the program?”

“You’ll know when the therapists say you’re ready to leave.”

Back then, I didn’t bat an eyelash, and working this way became second nature. It was like being in a cult. Only when I bought my plane ticket to Australia did I leave the cult and begin to understand how insane it had all been.

The World that Changed Me

Shortly after settling down with Renee, I contacted a local outdoor therapy organization and got hired. Quickly.

Australians, I soon learned, don’t think about psychotherapy in exactly the same way Americans do. In the United States, people often think that if you don’t have a manual or an acronymed approach to back up your interventions, you’re flying blind. But in Australia, especially in rural areas, many programs don’t require degrees, offer manualized treatment, or rely on evidence-based practices. Checks and balances are virtually nonexistent.

Given my near-immediate hiring, it was clear that my new employer thought I had some kind of wisdom to impart. The way I spoke about therapy not only made me a bright-eyed novelty, but an anomaly. Just two weeks into my employment, I was told I’d be leading the program’s first week-long expedition, comprised entirely of Indigenous teenagers.

These teenagers lived in the harsh wilds of the outback, in disadvantaged towns, where feral dogs roamed free, and burned cars lined the side streets. The Indigenous population had been relocated here by the government more than a century ago and essentially ignored.

Many of these young women had suffered unspeakable trauma. One suffered from fetal alcohol syndrome, which had resulted in developmental delays. Another had a boil on her leg that would eventually require hospitalization. Almost all were survivors of sexual assault.

But their school, which had contacted my employer to schedule the expedition, didn’t see them this way. These were the “naughty kids,” the teachers told us. They skipped school, talked back to authority figures, and abused substances. Apparently, they were disengaged and troubled.

A part of me felt up to the challenge. After all, I had my social work degree and extensive training. But I had my doubts, too. Here I was, a white man from Washington, DC, sent to treat a group of Black Indigenous women in their home, a place I knew virtually nothing about. It reeked of colonialism. I knew I’d need to tread carefully.

Far from Home

As the girls and I began our hike across the Flinders Ranges, I began to feel a little lost, but not geographically. There’d been no strip search before we embarked. My supervisors back at base camp hadn’t given me any instructions to take away belts, shoes, or sharp items, or to monitor conversations. Even if I wanted to listen in, the girls usually spoke in their native language, which I didn’t understand. We’d have to make do with hand gestures and what little English the girls spoke.

About three hours into hiking, I noticed the group beginning to lag behind me. I turned and saw the teens had adjusted their pace for Rebecca, the smallest one, who was wilting under the weight of her pack. Then, a few began taking her heavier equipment on themselves. “Now we can all stay together,” one of them told me with a smile.

There were other moments like this. Rachel filled everyone’s water bottles. Isabella asked regularly if anyone needed to take a breather. And Francine shared how her father had taught her to navigate with a compass.

That afternoon, during one of our intermittent water breaks, a few of the teens broke off pieces of wire from old fencing along the trail and began to draw in the red dirt. Crouching down, I watched as they drew pictures of their village.

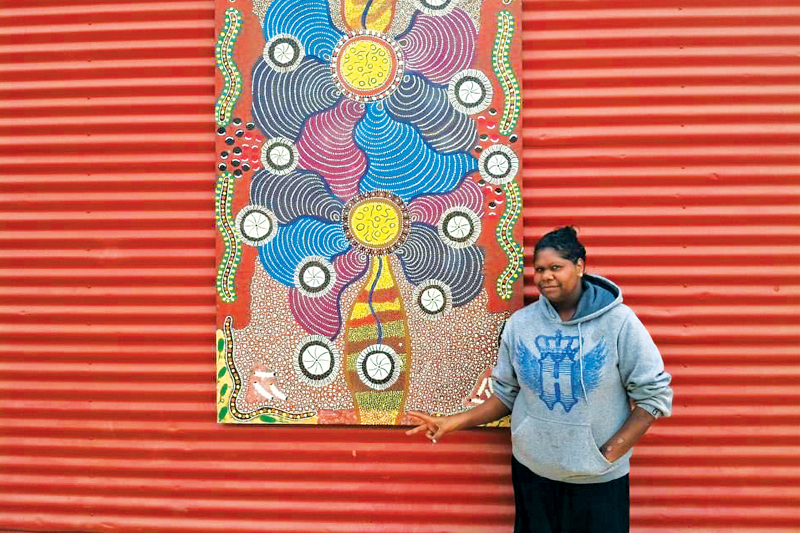

“We draw like a bird would see it, you know?” Carol said, referring to the dot paintings her culture is known for.

“Over there, that’s my home,” said Francine, pointing to a box she’d drawn filled with lines representing her family members. I counted seven.

“Wow, that’s a big family!” I exclaimed. “I’ve only got one brother.”

“Five brothers and sisters,” Francine replied. “My father’s in jail, so I watch them when mother’s working. I cook the food. I change baby’s diaper.”

Seeing the expressions on the other girls’ faces, I knew she wasn’t the only one in this predicament.

I picked up a piece of stray wire and tried drawing my childhood home, also from a bird’s eye view. It wasn’t pretty.

Francine let out a deep belly laugh. I did too.

- - - -

At our campsite later that night, we gathered stray pieces of wood and threw them into a big pile. Therapist Sarah showed the group how to start a fire with flint and steel.

As the fire crackled to life, everyone took a seat around it and began to pick at the stew we’d prepared together. I’d learned to use these quieter moments to capitalize on the day’s successes, to draw attention to the participants’ strengths. “So, how’s everyone feeling?” I began.

“I’m exhausted,” Carol said.

“My shoulders are killing me,” Francine chimed in.

“But you did great, too,” I offered. “What helped you get through it?”

“When I got tired on the hike, the other girls really helped me keep going,” said Rebecca.

“That’s great,” I responded. “Is there anyone else in your life back home who also encourages you like this?”

“I live with my auntie and uncle,” Carol said. “They’ve never given up on me. I should probably be nicer to them, because they’re doing everything they can to help me.”

“What do you think they’d say if you told them how much their help means to you, the way you tell the girls here you appreciate them?”

Carol sat silently as a tear rolled down her cheek—a tear of grief, perhaps, but also one of gratitude. I could tell she wished she’d been kinder to them.

Francine broke the silence. “My boots hurt the whole time, but I was still having fun and laughing,” she said.

“And how were you able to do that?” I asked.

“I was reminded of the strength of my mother, of my ancestors.”

I nodded. I’d learned over the years that people attach their own meaning to experiences, even simple ones like hiking.

“We’re fighters,” Francine said, rubbing Carol’s back as she dried her tears.

“Let’s call ourselves the Warrior Women!” Rebecca exclaimed. The others nodded excitedly.

I couldn’t help but smile.

- - - -

That night, after we’d had our fill of tea and the campfire embers flickered weakly in the darkness, the girls began to head to their tents. Rebecca was the last to leave the circle.

“Hey, Rebecca?” I ventured.

“Yeah?”

“It was really cool watching you navigate today. Even though you had to slow down, I thought it was great you asked for help. Asking for help is a good thing that can help you in lots of situations. I can’t wait to see more of that tomorrow. Have a great sleep.”

Rebecca smiled. “Thanks, you too.”

It had been a good day. An unusually good day. But why? I wondered. I hadn’t done—or needed to do—much at all. I hadn’t pulled from my bag of empirically supported therapy techniques, conducted any in-depth clinical assessments, or made any diagnoses. More importantly, with only Sarah and myself leading the group, I hadn’t had the time nor the energy to monitor conversations or check the girls’ packs for harmful objects. So be it, I thought.

Then, under the sky, peppered with stars, I watched as the girls scooted their tents closer to Rebecca’s.

It was like a lightbulb had gone off in my head. That’s it! I thought. These girls were the experts here. Despite experiencing horrific trauma,

they were fun, caring, and strong. Together, they knew how to keep each other safe.I hadn’t needed to tell Carol she should be kinder to her auntie and uncle. She’d come to that conclusion herself. I hadn’t needed to comfort Rebecca, either. She already had a community to support her. All I’d done was allow these young women the space to demonstrate their strength and resilience, away from the distractions back home. Maybe, I thought, that was enough.

That night, I hardly slept. That revelation marked a turning point in how I viewed not only my role as a clinician, but the purpose of therapy itself. Over the next few days, unfettered by manualized treatment protocols and seeing how my clients could find their own answers without excessive rules and supervision, I began to question everything I’d been taught.

- - - -

Over the next week, I felt reborn. As the group and I walked over rolling hills and past old pioneer huts, we traded stories. I learned that one of the mountains we’d pass, a leaning, triangular rock formation that sheltered the ground beneath, was where Indigenous women had walked thousands of years ago to give birth. I told the women about the places back home that were important to me, too. As the setting sun scattered red, pink, and orange light across our path and wedge-tailed eagles flew from the gum trees overhead, it felt as if the land had come to life.

On one particularly hot day, we came across the muddiest, reddest watering hole I’d ever seen. Almost immediately, the girls threw off their packs and charged in, playing, splashing, and screaming with delight. I caught my tongue as I started to call them back. They’d earned this, after all. After so long, they finally had a chance to be uninhibited and carefree, to have a piece of their childhood back again.

“I don’t want to go home,” Carol said on our last day together, putting the finishing touches on my face paint—in the red, yellow, and black colors seen on the Aboriginal flag.

“Me neither,” said Isabella. “I’m going to miss sleeping under the stars.”

But our trip had come to an end. The teens got on the bus and drove home, and my team and I began the short walk back to base camp.

I was exhausted. That night, I slept more than I had after any other expedition.

- - - -

Six months later, Sarah and I drove to the girls’ village as part of a scheduled follow-up visit. When we arrived at their school, one of the teachers ran out to give us a big hug, the principal not far behind.

“Everything has changed here,” she said with a smile.

One by one, the girls came running out, tugging at my arm to show us their home.

“We’ve kept the Warrior Women group going!” Rebecca said enthusiastically. I soon learned from their teachers that Rebecca had been awarded a scholarship at a prestigious boarding school. Isabella had worked up the courage to leave an abusive relationship. Rachel was volunteering at a local childcare center, and Carol was training to become a community police officer, both so that they could protect the community they loved.

I don’t flatter myself to think the expedition was directly responsible, but I like to think that maybe it gave them the nudge they needed to take the next step. Maybe, I thought, it gave them a chance to see themselves at their best, to challenge the narratives they’d been told about who they were.

As the sun began to set, some of the children from the village lined up to perform a dance. When a few elderly men gathered at the gated entrance and began to heckle, several of the girls stepped forward, stood up strong, and yelled back as the men scampered away.

My eyes welled with tears. It was everything a therapist could wish for.

The Reformed Outdoor Therapist

Looking back, I realize my journey is complicated. As formative as it might’ve been, I think back on the work I did as an outdoor therapist back in the States and shudder. Of course, sometimes these programs did help. But mostly, they were demoralizing. Not only did they often fail to treat trauma, but they sometimes made it much, much worse. Giving clients information about the therapy agenda and a sense of choice are essential for healing.

Back in the States, I wasn’t trained how to roll with the angry kid or sit with someone who felt hopeless. I was trained to make sure they complied with the program. Sure, our intentions were good, but we imposed our worldviews of risk onto these kids. In the name of safety, we took away their dignity.

Still, I know I wouldn’t be the therapist I am today, committed to abolishing so many of the practices these types of programs support, without having lived in two worlds. When I began my career, I didn’t know the harm that could come from blindly following a manual without fully acknowledging the client in front of me. Now I do.

Like every therapist, I’m a work in progress, and I’m trying to do better every day. I realize now that I do my best work when I decenter therapy, when I take myself out of the equation as much as possible and guide, rather than instruct. And I always invite the worldviews and knowledge of those I work with into therapy.

After finishing my graduate degree in social work, I founded a nonprofit, True North Expeditions, Inc., in Adelaide. I know that no teen decides to enroll in my programs by choice; most are forced to attend by their parents. But I tell every client that I care only about making this experience useful for them, and that I welcome feedback if they ever think I’m off track.

I’ve changed. And I like to think that, maybe, our field can change, too. I wonder what a wider embracing of alternative methods like outdoor therapy might mean for our society, especially for disenfranchised and forgotten people. I’ve watched clients challenge themselves in ways they simply can’t in an office once a week for 45 minutes at a time. Psychotherapy needs alternatives to the century-old approach of sit and talk, not more of the same. When you’re open to the spirit of adventure, you never feel stuck.

***

Will Dobud, PhD, is a social-work lecturer with Charles Sturt University and the founder of True North Expeditions. His research centers on client experiences in therapy, indoors and out, and how therapists can improve outcomes. He’s also the South Australian state representative of the Australian Association for Bush Adventure Therapy, as well as the 2021 Distinguished Researcher of the Year for the Association for Experience Therapy. Contact: wdobud@csu.edu.au.